Hey, I’m Elise,

and I’ve spent the better part of a decade exploring how biology, design, and innovation can shape a more sustainable future. It all started with a simple question: What if our materials could grow and adapt like living organisms do?

That curiosity led me to study fungal networks, experiment with mycelium-based engineered living materials, and partner with forward-thinking biologists, engineers, designers and artists.

As an architect, I learned to build stable structures that do not collapse. The materials I was trained to design buildings with were lifeless and silent. They had no memory, no metabolism. Until, years later, I held a piece of mycelium material in my hands. I had grown it myself from a mushroom I had found in the forest. I discovered that it could repair itself, that it responded to light, moisture, and heat. I realised that what I was building was no longer an object, but an organism I had to take into account. A being with its own whims and needs.

Despite my ten years of experience with living materials, I often still felt like an outsider among biologists. A designer in a biolab continues to raise questions. Even simple actions are sometimes met with suspicion. With every contamination, I feel responsible, as if I must once again prove that a designer can be just as precise, careful, and reliable as any other researcher. In many academic laboratories, it is difficult to find space for the trial-and-error approach on which design research thrives. My creative process begins with prototyping, failure, and iteration. These are methods that are self-evident in the arts, but in microbiology are sometimes seen as careless or inappropriate. “This is a microbiology lab, not a prototyping lab,” someone once told me, as if those two worlds were mutually exclusive.

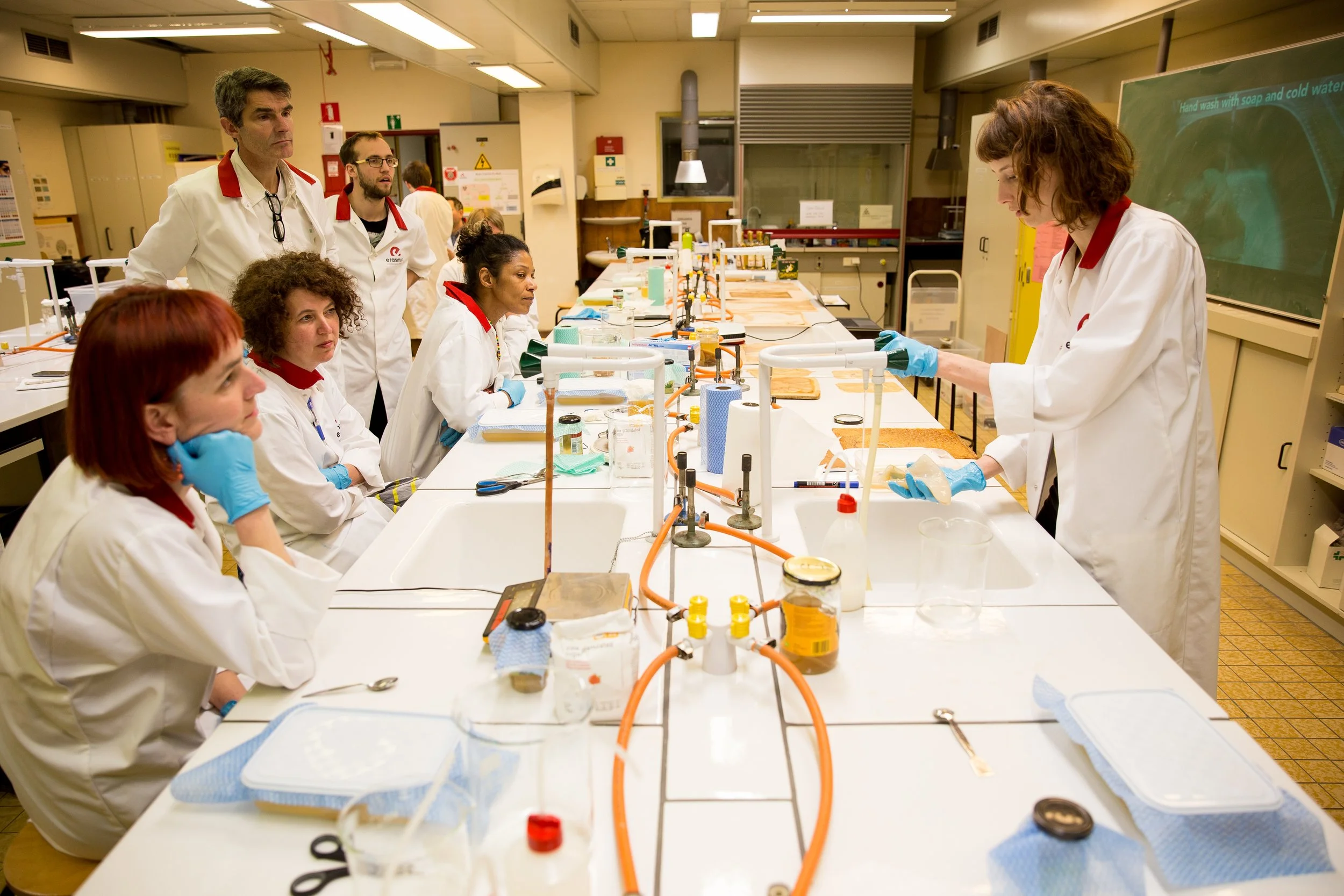

Ultimately, these experiences led me to create an interdisciplinary laboratory within the Microbiology research group at the VUB. Since then, I move between disciplines in a lab where biologists, materials scientists, designers, (bio)engineers, and artists come together. Between these worlds, I try to speak a new language: one in which measurement and imagination do not exclude one another, but strengthen each other. My work is a continuous negotiation between order and unpredictability, between control and trust. Science gives me precision: the ability to understand conditions, to steer light, moisture, and nutrients. Art gives me the freedom to search for meaning in what cannot be controlled. Between the two, something new emerges: a field where experiment and imagination converge, where a material is not dead but alive, not fixed but in the making. A place where symbiosis is not a metaphor, but a method.

I work with organisms that live together: fungi, algae, bacteria. Each with their own rhythm, their own logic. I do not see them as instruments, but as partners. They are collaborators with their own form of intelligence. They teach me about boundaries: between species, between life and non-life, between nature, the laboratory, and the built environment. In this way, a different idea of sustainability grows—one based on reciprocity. Materials that feed themselves, that learn to cope with drought, light, and time. An architecture that continues to change.

In traditional production processes, form is often given to a product only in the final stage. This approach does not work with living materials. Design is embedded in the growth process itself. From the moment a designer chooses the substrate and sets the environmental conditions, crucial decisions are already being made that determine how the organism will grow, which structures will form, and ultimately what the material will be able to do. Every fluctuation in temperature, every subtle change in humidity, every added nutrient becomes part of an active design dialogue between human intention and microbial agency. In the research I write and carry out, I try to shift the formative capacity away from the designer and towards the living system itself. We become merely co-designers with the living organism. That requires a different kind of engineer or scientist: one who learns to share control and is willing to guide without determining everything, to create conditions in which the organism can find its own form.

I believe that science and art together create the possibility to reimagine our relationship with the living. Science makes visible how complex and entangled life truly is. Art allows us to feel what that entanglement means. Together, they open a space in which materials can function as living ecosystems: autonomous and in continuous exchange with their environment.